By Elina Nygård, Ájtte, Swedish Mountain and Sámi Museum

Ájtte, Swedish Mountain and Sámi Museum in Jåhkåmåhkke wishes to share insights into the process of curating and building exhibitions about a sensitive subject for a minority. The museum opened in 1989 and tells the Sámi history, from the melting of the inland ice until now. Ever since the initial planning of the museum, one perception has been of great importance: Ájtte is a place where we as Sámi people tell our own story. The exhibition at Ájtte museum plays a role not only as a place where you as a tourist can learn about the indigenous people of Scandinavia (where the common level of knowledge is quite low) but also as a place for building identity for Sámi people searching for their roots and learning about their own history.

Over time, Ájtte museum has earned trust from the Sámi society to communicate the stories in a proper manner, in a Sámi way. This is expressed in different ways: for example, all our texts are written in Sámi as well as other languages. The architecture of the museum derives from a keystone of the Sami culture, a reindeer corral, whose symbolism indicates that we tell our own story. We strive to protect the integrity of the stories and storyteller, and to keep the stories safe for generations to come. This is an ongoing discussion at the museum – how to treat the material with respect. Since we are a small group of people questions about anonymity are particularly tricky. It´s often not difficult to guess where the information comes from.

Historical context

The historical narrative in the museum starts when the inland ice melted 11,000 years ago. When going towards the centre of the museum you walk through “The passage of time” where you face people from different generations until the present. You meet hunters, fishers and reindeer herders, and learn that the land and water has fed us through history, right up until now. We lived here in Sápmi, the land of the Sámi people, long before the national borders between Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia existed, and moved with the reindeer between different grazing areas. During the last centuries we have gradually been pushed away due to shipping, mining and forestry. The right to land and water is a burning conflict in today’s society and the indigenous people’s traditional rights are constantly questioned. Reindeer herders have to make do with the limited land that is left and at the same time always be prepared to defend their right to the land against other interests.

In Identity on the Line we focus on a land-loss story that happened a hundred years ago, of which we still feel the consequences. Due to border politics we lost our traditional grazing sites by the Atlantic Ocean. The land was supposed to be used by Norwegian farmers instead. Sweden relocated families and reindeer to areas on the Swedish side of the border to deal with the problem. But other reindeer herders already lived on those areas. They wanted to keep their traditional land, but had to make room for the newcomers. The conflicts that arose then still have an impact today. The grazing land is decreasing as we speak.

The project and background material

When we were asked to participate in the project Identity on the Line we had already been in contact with the journalist Elin Anna Labba, who wanted to cooperate on an exhibition. For years, she had been conducting interviews among her relatives and other north Sámi elders that were forced to move to a new place as children or babies. Many touching stories were shared with her during these interviews. Eventually it became a book Herrarna satte oss hit (The High Lords Put Us Here). When it was released her availability to participate in the project changed. The book became a success and she won the August Prize, one of the most prestigious prizes for authors in Sweden. However, she has functioned as a reference and provided guidance throughout the project.

With Elin Anna’s book as a foundation we wanted to look at migration from another point of view. What about the people that already lived on the land? What about their thoughts and feelings? Jannie Staffansson started to work in the project together with Elina Nygård. Both Jannie and Elina have ties to the forcibly relocated; Elinas’s family share the story of being forced to leave the north, and Jannie’s family moved to Eajra shortly after others had been forced to leave. Having networks in the north-middle Sápmi and in the south Sápmi provided us with better coverage within the project. It allowed for a wider perspective on the subject and knowledge about other forced relocations that have not been spoken of much.

Ájtte maintains a Sámi library and keeps stories, handicraft and interviews that have been conducted by a number of people in the past. In the archive, we found old yoiks and stories, in Sámi languages and in Swedish. From this vast knowledge base, we collected information for the exhibition.

“For indigenous peoples, it is important that it is our own institutions that tell our own story, to control how to communicate and gather information, so that the process is done in line with our customs. That can only be done by our own people.” says Jannie Staffansson.

Inherited trauma

Since our foundation for the planned exhibition was to focus on the personal stories, our goal was to open up a process of receiving more stories. Creating a space for untold stories and providing space for people to tell them in their own way, in their own voice. However, there were not many people willing or able to talk about the forced relocation. And even fewer of those Sámi that were already on the lands when the relocated arrived.

Some informants that were hesitating were not sure if they remembered well enough, or knew enough. They said that they themselves may not have experienced the relocation, or were very young when it occurred. Or that they only held fragments of the story, that we were too late conducting the interviews.

“The ones that you should have interviewed have passed on already”.

When we reflect about why, the reason might be that the story is unwritten and scattered in small pieces. Perhaps different informants had different fragments. The story had to be created in common. Some were asked if they would be interviewed in a group of others, which they agreed to. The informants got a transcription of the interview afterwards and the ability to change it or explain further. Then they were asked to meet again and talk further, which some of them did. And even if it was demanding they felt good about doing it. They felt that it was important that the story was told. Before the stories were included in the exhibition they got to hear them and give agreement, as well as to decide if they wanted to be anonymous or not.

We also tried to get younger people to be interviewed and reflect on whether the forced relocation had affected their identity. That was also difficult. Many felt like they had nothing to say because they didn´t know enough. The people willing to speak were individuals who had done lots of research on the subject and already reflected on it for many years. Since the topic is connected to the heated discussion about the right to land and water, perhaps people feel that they need to be sure about the historical facts before they start talking.

To provide more comfort to the informant we wished to let them speak their own language, so we needed different interviewers who spoke different Sámi languages. To share stories of trauma, the informant needs to remember the trauma or stories of the trauma that others have gone through. That is not a pleasant situation and often quite demanding. For us it was important not to put a language barrier on top of that, it is important to be able to express yourself in the language most natural for you. Another ingredient for comfort is coffee. Conducting interviews in a Sámi way involves either being outdoors, around a fire, drinking coffee, or sitting at the informant’s kitchen table, drinking coffee. Both involve sharing a safe space where the person can be interviewed.

The form of the exhibition – ideas grown from Sámi artists

What is an exhibition? What can you do with it that you can´t do with a book or a film? First of all, we have a space that we can use to provide an experience for all our senses. We can fill that space with items to strengthen our message, to create an environment filled with things that speak to all our senses. Old things from the museum collections, as well as new things created for the purpose. We can use sounds, different materials in different levels. We can use lights, texts and pictures to build up emotions. Even smells, which is said to be the best sense to bring back memories.

When we planned for the exhibition we had some key words in mind: Invisible stories, people’s own voices, colonisation, decolonisation, identity, respect.

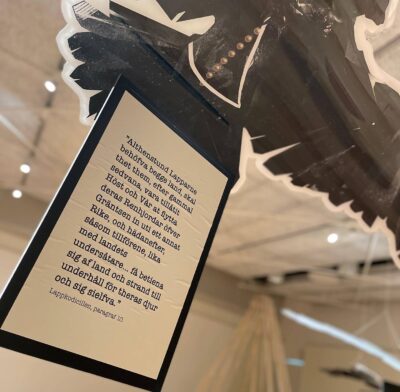

In the Sámi culture the traditional place for storytelling is by the fire inside the gåetie. And so the centre of the exhibition is a fireplace with a display where you can choose stories, both from the archive and newly recorded, and hear people’s own voices. Sound files and written quotes are the foundation of the exhibition. The messages and quotes from people in power come from above. The roof is filled with big ravens, dressed as policemen, holding messages from the king/state. The inspiration to the birds dressed as police officers comes from a famous Sámi artist, Britta Marakatt Labba, who embroidered a famous piece about Sámi resistance.

Beneath the ravens there are quotes from the people that were affected by the words of the ravens. These are printed on transparent showcases with an object connected to the subject inside. This transparent theme is inspired by another famous Sámi artist, Tomas Colbengtsson, who works with glass. We were inspired by his art and wanted to use his artistic idea as a foundation for the exhibition, since we are talking about making invisible stories visible. Tomas was glad to cooperate with us and we were in contact with him several times during the process. One of his glass sculptures, a south Sámi women divided in the middle, can be seen in one of the exhibition showcases. His voice can also be heard in the listening station. Tomas writes in his book Faamoe (meaning Strength) from 2019:

“In my art, I reflect upon how our colonial heritage has changed our lives and the northern landscape. The same processes and mechanisms that affect indigenous people wherever in the world we are. Perhaps my loss of language is the main reason that I work with glass.”.

Both Britta and Thomas were spoken to at an early stage, while developing the idea for the exhibition. We kept in mind to have artists from different parts of Sápmi represented.

As a visitor to this exhibition, you start beside a half gåetie (Sámi house), where the structure is made of acrylic tubes, almost invisible traces from the old land. You get an introduction together with the message that you are welcome to share your own story. Then you follow an invisible raiddu consisting of sledges which used to be pulled behind reindeer. As soon as you come close to one, a voice will start talking, you will hear something about the theme in the Sámi language, which will also be printed on the sledges in Swedish. At the end of the raiddu you will end up in a visible gåetie with a fire in the middle. This is where you shall sit down and listen to the personal stories and reflect on them. Outside this gåetie there will be display cases with different themes: Sámi stories from different areas, as well as stories about forced relocations of other indigenous peoples around the world. Above every display case there is a big raven with a message in it claws. Each display case contains an item connected to the story as well as a quote printed on the tube from an individual affected by the relocation. Before leaving, you will see a big colourful painting done specially for the exhibition. The artist Lena Viltok also wrote a poem. It is about the first meeting between two groups of Sámi, inspired by a story found in the museum archive.

Choosing a language

It is always tricky choosing a language when constructing Sámi exhibitions. In Sweden we have five different Sámi languages, all of which are threatened due to the small number of speakers. Almost all Sámi people in Sweden speak Swedish, since it used to be a colonisation strategy to forbid children to speak their native language, even in the Sámi schools. If we chose Swedish as the written language in the exhibition, most people would understand. At the same time, if we wanted to raise up our own language and heritage (and of course we would like that) which Sámi language should we use? As soon as we chose one it would mean we were not choosing four others. To keep the focus on the subject, we chose to print all the quotes in Swedish in the exhibition and translate them in to different Sámi languages (as well as English) in accompanying guide texts.

Reactions

In late 2020 we made a film presenting the exhibition, which was shown at a digital winter market in February 2021. We got mostly positive feedback from the audience. Many said that it is a good thing we are doing, since many know so little about the subject and that the exhibition looks beautiful. One of our elders felt sorry to see the invisible sledges and said

“The Sámi culture has been made invisible for so long, and now that it´s finally starting to become visible you are making it invisible again. I don´t like it.” A younger person said “It was so strong and beautiful; I started to cry when I saw it.” Another reflection from a younger person was: “Now I know why I like it by the ocean. I´ve always longed for the ocean. The first time I arrived at Senja (Norway)… I never felt so at home at any place in the world before. Later on I found out that this was the place my old relatives left. I didn´t know about it then.”

We finally opened the exhibition in February 2022. At the moment of writing, when the exhibition has had a couple of hundred visitors, we have had lots of positive feedback. In the evaluation, the focus group found it very important and interesting. They thought it was important to talk about the subject. On the other hand, we also had response from a visitor that thought that we should not focus on this kind of subject, that tensions may arise among different Sámi groups and that it would be better to keep quiet about it, and focus on the future instead.

MAIN CHALLENGES

The global Covid-19 pandemic

When the obstacle of finding informants was overcome, the world was struck by the pandemic. Since most of our informants are elderly and/or in risk groups we needed to reschedule the meetings. Some of the interviews were performed in the autumn outdoors when distance could be maintained, and some indoors with larger distances. The technical solution of interviewing online was unthinkable with this type of topic. Instead of doing interviews we searched the museum archives. We found some interviews, a few yoiks, pieces of stories in many different books and newspaper articles. We ended up postponing our exhibition opening, not only once, but twice.

Translations

The stories we gathered were from different areas within Sápmi. In our exhibition we wished to have them translated into the Sámi spoken in that area, which proved to be very difficult.

The Covid-19 pandemic affected us yet again, since some of the translators got ill. Some languages are only spoken by elders in far off communities, and some translators into the smaller languages were overwhelmed by work.

A further challenge is to take the experience this project has given us and apply it to the ongoing process of improving as an institution. We need to ask ourselves what a Sámi way of curating exhibitions might look like in the future and how to best stay true to the role we have as a Sámi museum, and as always, ensure our voices are heard.